It is always gratifying to get stories of “Fred” and “Fred Sightings” from people around the world. Time and circumstance don’t always allow me to share, but the following is a submission from my new friend Shala that I think you’ll find informative and inspiring.

to share, but the following is a submission from my new friend Shala that I think you’ll find informative and inspiring.

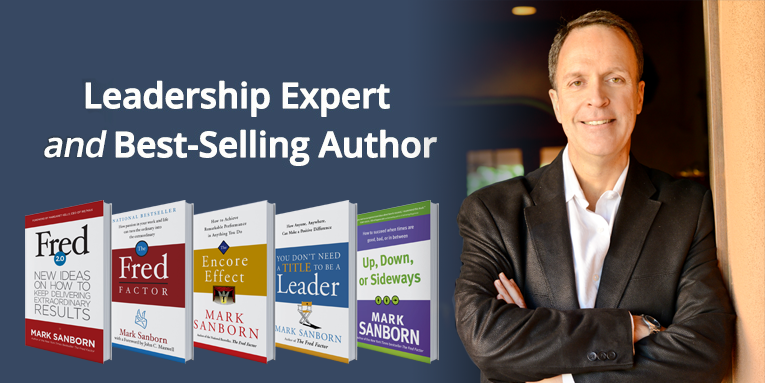

When I first came to know Mark and his book, “The Fred Factor,” I remember recalling my own Fred story and wanting to write it all down and send it his way. But I figured “he must get a lot of these” so I held off. A message from one of his Twitter followers requesting to hear other Fred stories prompted me to finally send mine. And so, in honor of the ebook release of Fred 2.0 this week, I’m sharing my “Fred” story.

At the beginning of October 2010 I was mid-way through training for a marathon – the NY one to be exact. I was about to switch jobs and had begun my application for business school. By all accounts I was full steam ahead on my own course. By the end of that month, however, my life and its accompanying choices would look very different. An unknown pre-existing condition combined with a seemingly innocuous drug would win me no-less than a three week stay at Georgetown hospital – just the beginning of my medical journey – and my first encounter with their incredible nursing staff.

Nurse Nick was assigned to me when I was first admitted for a “pinched nerve in my right arm.” Now I had come in to the ER with a few of my guy friends – we’re a jovial bunch and this sounded like quite the field trip. Nick blended right in, cracking jokes from the very beginning. When I eventually found out that that I had a large blood clot in my right arm, and when it came time to learn how to administer shots, Nick didn’t skip a beat. He looked at me, grabbed a piece of fat from his belly, and made a piercing motion and a funny face. I was halfway between cracking up and being horrified. My guy friends loved it. To be sure, Nick’s sense of humor went above and beyond and cushioned the blow of bad news. Delivery really is everything.

I would see Nick again on subsequent ER visits. He made a special effort to pop by my ER cubby whenever he saw my name on the roster, checking-in on me whether or not I was “assigned” to him. He never forgot a detail about my case, and was always there to lend a laugh. He was, by all accounts a “Fred,” but he wasn’t the only one wandering around Georgetown Hospital as I would come to find out.

What they don’t tell you when you get sick is that the bulk of your time and mental energy, for the most part, is actually spent fielding the emotions and fears of others, with the exception of a select few. I don’t say this in an ungrateful way – I felt a groundswell of support. But bad news is tough to deal with when it comes in the form of multiple pulmonary embolisms and organ failure. So you put on a front of outright joy to compensate and reassure those around you. In essence, when you are really sick, the hardest time in your life simultaneously becomes the point when you race to claw through emotional quicksand towards happiness like your life depends on it – because it does.

I say all of this because I think that nurses have a way of knowing this reality and accommodating for it. For example, the end of the day at the hospital, when visiting hours had come and gone, was always my worst and best time. It was blissful to finally be left alone in my thoughts, and miserable for that very same reason.

Alone with the beeping machines and its wires; with track marks covering my arms, hands, and feet from having my blood drawn over and over.

Alone in silent gratitude for still being alive.

Alone to process the bad, the ugly, and the scary.

Maybe the Georgetown nurses just have a sixth sense about this time of the night in hospitals. But when this time would come, one would enter my room, sit with me, and hold my hand. They wouldn’t talk or make me explore the emotions. I felt free to feel whatever around them – sad or scared – they just let me be. I’ll never forget how precious this silent time was and believe it helped me recover for the next day of doctors, needles, fielding family emotions, and bad news. Now I haven’t looked at a job description for nursing lately, but I imagine it includes following requisite medical procedures with patients, filling out mountains of paperwork, and general bedside manner. I doubt it is so specific as to include holding a patient’s hand, sitting beside them, and silently acknowledging their fear with kindness and empathy. At this point I could care less about the formal description, the latter peripheral actions were pivotal when it came to keeping me mentally together to make it through the long haul.

I was in the NICU a few weeks ago with my sister and her newborn child. At the time, my nephew was hooked to an abundance of wires and after four days she still hadn’t had a chance to hold him. It was clear to the nurse that she was dying to. In recognition of her maternal pain (and what was good for the baby), the NICU nurse proceeded to swaddle him up in an extra special way to give her a rare chance to hold her child. It was a privilege to be in the room to witness this beautiful moment and I’ll never forget it. That nurse could have executed the last part of her administrative duties for the day and walked away, but instead she went over and above to ensure that my sister, scared after having to be in the NICU anyway, could have a meaningful moment with her child. That moment made me think of Nurse Nick, Fred, and all those who go above and beyond in executing their job with love and care, especially in the nursing field. I remain in awe of nurses, and forever will. They are my “Freds.”