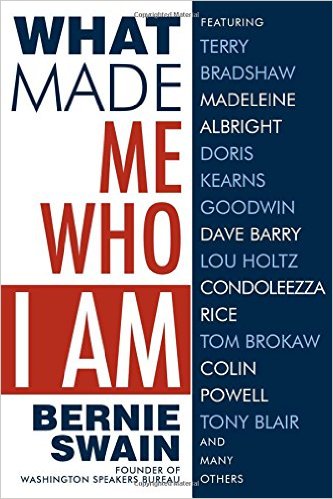

Over 25 years ago when I was a young speaker in the business, I met Bernie Swain and Harry Rhoads, the founders of Washington Speakers Bureau. They were then and are now true class acts, and they were very supportive and helpful early in my career. Bernie has written a great new book about the many fascinating people he’s booked over the years and the lessons he’s learned What Made Me Who I Am. What follows is a guest blog Bernie wrote about another favorite of mine, Terry Bradshaw.

Over 25 years ago when I was a young speaker in the business, I met Bernie Swain and Harry Rhoads, the founders of Washington Speakers Bureau. They were then and are now true class acts, and they were very supportive and helpful early in my career. Bernie has written a great new book about the many fascinating people he’s booked over the years and the lessons he’s learned What Made Me Who I Am. What follows is a guest blog Bernie wrote about another favorite of mine, Terry Bradshaw.

Fall is back, and with it football—along with all the sports metaphors and lessons that we hold dear, about what it means to be a team player, about not giving up in the face of terrible odds, about how much it takes to be a leader.

Terry Bradshaw gave life to those lessons as much as anyone in the years in which he starred as the Pittsburgh Steelers quarterback before embarking on a second successful career, in sportscasting. The struggles he went through on the way to his success—and how close he came to missing out on it—always come to mind for me at this time of the year.

Many fans have forgotten, but Terry had a very rough transition to professional football after his college years at Louisiana Tech. In Pittsburgh, he was initially tripped up by a volatile mix of bravado and self-doubts, then lost touch with his talent and quickly went from hero to pariah. He found his way back by swapping his hubris for humility, settling into a team role, and reconnecting with his strengths while accepting his limitations.

Terry told me about the pain and confusion of this early chapter in his career in the course of conversations I had with many leading players in politics, business, the media and entertainment, in addition to sports. I represented all of these people during my 30-plus years at the Washington Speakers Bureau, a firm I co-founded and built into the leading lecture agency in the world. Though my clients were all successful by the time they signed up at the agency, that wasn’t always the case during their earlier years and I became curious about the turning points that had proved so important to them.

In Terry’s case, the way he overcame his rookie missteps offers a playbook that we can all use off the field—to harness the power of self-awareness, and the acceptance of criticism (from others and ourselves), to better ourselves and our performance and perhaps even to secure a leadership role.

When he arrived in Pittsburgh as the top draft pick in 1970, Terry found himself out of his league, unprepared for the pressures of professional play.

“I thought I could win games by myself,” he recalled. But he was undisciplined and thin skinned—he bridled when the media called him a country bumpkin from a backwater school—and he resisted learning to play the Steelers way. “Instead of trying to adjust, I rebelled,” he said. “Being the number-one pick had swelled my head so big it forced the common sense out. If the coaches wanted me to go right, I ducked left.”

Inevitably, he got into trouble with the fans and the press as well as the coaches. And, worse, he was no longer in control of himself—“I threw and played erratically”—and got benched a lot. “I’d sit there on the sidelines, miserable and misunderstood, wondering how the hell I ended up in this place.”

The misery ended when he realized that he was, in large measure, the source of his problems, and that he had the power to fix them. “One night, I sat in front of my TV, crying my eyes out, filled with shame. Something in me told me that I had the key and title to my life, and shame on me if I allowed other people to steal that from me.”

And so he broke his own tackle and pivoted into the middle of the field, where his teammates were waiting for him to lead. He studied the Pittsburgh playbook and took coaching to heart. He dropped his defensive attitude. And he refused to take the bait of critics, using humor to bat away their barbs. “I would beat them to the punch by making fun of myself first.”

He won back the fans and the other Steelers stakeholders. And he did it by embracing who he was, following the mantra he now often cites from Popeye, “I yam what I yam.”

“When I showed up in Pittsburgh, I was filled with insecurity and hubris, desperate to prove myself as smart and talented yet too arrogant to put in the work. I had to learn that it’s okay to be yourself, to be real, because then you don’t have to worry about convincing others that you are different.”

And in learning that lesson, he was able to reclaim his talents. “By my second season,” said Terry, who went on to win four Super Bowls, “I was playing pretty well.”